Back in Fort Kent, Jarrett Cannan spoke recently of his experience hiking the entire Appalachian Trail this summer. (Don Eno)

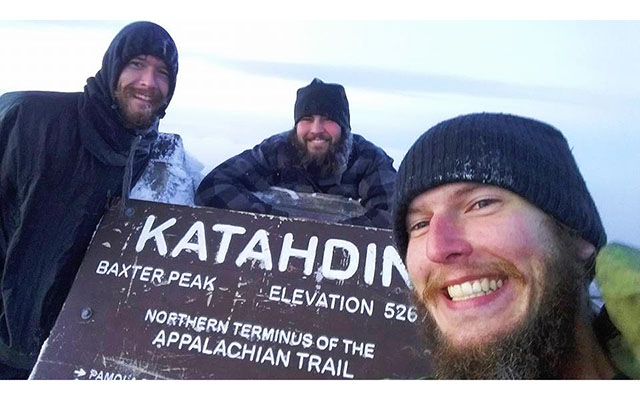

EAGLE LAKE, Maine — For one St. John Valley man, November started off with a special hike to the summit of Katahdin. The five mile hike from the campground trailhead to the large cairn at Baxter Peak was the final piece of a more than 2,000 mile puzzle for Jarrett Cannan.

The 25-year-old solar panel installer at ReVision Energy and native of Eagle Lake, who now lives in the Unity area, completed his hike of the Appalachian Trail on Nov. 4.

“It was awesome,” Cannan said recently while sitting in Rock’s Dinner in Fort Kent, less than a week after completing his trek. “I recommend it to anyone who is thinking about it.”

In the immediacy of his accomplishment, Cannan said he would need more time to reflect on how the 2,000-plus miles had changed him.

“It was harder than I thought, at first,” he admitted.

- Jarrett Cannan, originally of Eagle Lake, stands atop Mount Kathadin on Nov. 4, the final stop on his Appalachian Trail hike. (Courtesy Jarrett Cannan)

The AT is a 2,180-mile long public footpath that traverses several states from Georgia to Maine. First conceived in 1921, the trail was pieced together and built largely by private citizens. Completed in 1937, the trail is now overseen by various federal and state agencies, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy and thousands of volunteers who help maintain it.

A few thousand people attempt to complete the trail each year. Some are thru hikers like Cannan, who try and do it all in one shot. Others do different sections each year.

Cannan’s path to taking on the long distance hike was, he admits, somewhat unorthodox.

“I hadn’t backpacked before,” he said.

Cannan is an outdoors enthusiast who enjoys hunting, fishing and canoeing. However, living on the trail for weeks and months at a time was be a new experience for him.

His preparation prior to taking on the AT challenge was less than exhaustive, he admits.

- Jarrett Cannan stands at the summit of Mount Moosilauke in New Hampshire during his journey along the Appalachian Trail this summer. (Courtesy Jarrett Cannan)

“I only started planning about two months before,” he said.

When he first told his mother and other relatives and friends of his intentions, they were surprised.

“I didn’t know if they believed me at first,” he said.

Cannan said he was inspired in part by a coworker who had completed the AT in the late 1990s, he said.

“He was always telling stories about it,” Cannan said. “It just seemed like fun.”

Friend and former St. John Valley native Ryan Michaud, who now lives in Georgia, gave Cannan a lift to the trailhead at Springer Mountain, Georgia, where, beginning on April 17, Cannan headed north.

“I took my time,” Cannan said. Unlike some who have recently attempted setting new speed records for hiking the AT, Cannan wanted to take his time.

A tradition on the AT is for hikers to be given a trail name. Sign-in books at trailheads and at shelters are filled with quirky names. Somewhere along the way, Cannan picked up the moniker “Bear.”

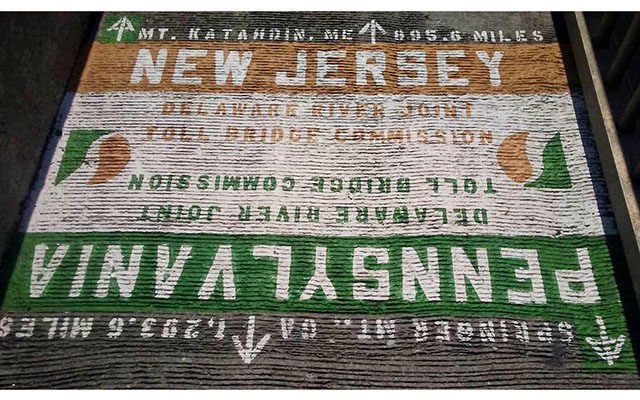

- This marker signifies the approximate halfway point along the Appalachian trail. (Courtesy Jarrett Cannan)

Cannan had planned his AT hike as a solo adventure. But, camaraderie on the trail is easy to find for those looking for it and he soon fell in with two brothers from Georgia who also were northbound (or NoBo in AT parlance).

He first ran into Adam “Stix” and John “Jangles” Phares in Georgia. Their paths would occasionally cross in the next few weeks and eventually the trio stuck together for much of the journey.

“We had the same kind of schedule,” Cannan said. “And, we were on the same budget,” he added with a laugh.

Cannan and the Phares brothers did not often splurge on large restaurant meals when they passed by a town and they opted for the maximum ratio of calories to cash.

“Dollar Stores were ideal,” Cannan said. Mainly, he would buy and carry four to five days worth of dehydrated foods. Family and friends also sent along care packages of food and supplies, mailed to key locations along the trail.

Consistent menu items included Pop-Tarts, ramen noodles and dried potatoes, Cannan said.

“You just stuff as much calories as you get,” he said. Burning through several thousand calories each day on the trail is common.

“I never made a bad meal on the trail,” he added.

For their first non-trail food after summiting Katahdin, Canaan and the Phares’ stopped at a McDonald’s.

“We each got five McDoubles, chicken nuggets, a milkshake and fries,” he added with a chuckle.

Cannan was able to find water on the trail and never got sick due to bad food or water, he said. He also never had serious problems with blisters, although his feet were very sore when he completed the trek.

He started off with boots, then switched to trail running sneakers. Eventually, he would go through four pair of boots and shoes by the time he was done.

The only medical issues or injury Cannan dealt with along the AT were occasional shin splints, which he said were very painful.

It didn’t take long for Cannan to figure out ways to lighten his pack load and make things easier on his feet.

“I lost 15 pounds of gear along the way,” he said. “You just didn’t need the stuff.”

These included items such as a journal, hammock, less rope and pants.

The Appalachian Trail is known for its occasional “trail angels,” who have helped weary hikers or have otherwise added unexpected kindness or something special to a thru hiker’s journey.

Cannan said he came across several such angels.

The one that sticks out the most in his mind, he said was Rebekah Anderson, owner of The Lakeshore House in Monson, Maine. Monson is the last town that hikers have access to before taking on the final 100-plus miles of the trail to Katahdin.

“It had been raining for a few days,” Cannan recalled. “We stood on her porch to stay dry. She saw us there and let us grab a shower. It was great.”

Cannan said that many residents in the towns along the trail from Georgia to Maine are used to seeing AT hikers, providing rides from the trailhead into town to allow hikers to resupply or even giving them food.

“There’s a really good community built up along the trail,” he added.

Although he would average between 15 and 20 miles on most days, Cannan admits there were times when he slowed down to enjoy and explore.

“I took a lot of time off at first,” he said. “I took 60 zero-days in all.”

A zero-day is when a hiker racks up, basically, no miles for the day. That nonchalance gave way to a bit more haste, though, as Cannan saw the season heading quickly toward fall and Katahdin still a long way off.

“It’ good to be home,” was Canan’s thoughts, he said, when he finally crossed from New Hampshire in Maine.

Sleeping accommodations on the trail were minimal for Cannan, who carried a tarp and sleeping bag.

“Most nights, I’d sleep under the tarp,” he said. “If it was raining, I’d use a (lean-to) shelter, if there was one.”

Cannan considers the White Mountains in New Hampshire as probably the most scenic and spectacular setting along the AT. With its numerous peaks above 4,000-feet, much of the white-blazed AT here traverses terrain well above the treeline.

The Grayson Highlands in Virginia, the Smoky Mountains and the Shenandoahs also were beautiful, he added.

Following their final hike up Katahdin the trio came to Fort Kent, where the Phares brothers visited with Cannan’s family. The Georgia brothers headed back home via bus on Nov. 10.

Cannan said he is not sure if he will attempt another long distance hike, such as the Pacific Crest Trail or the Continental Divide Trail.

“This was a lot of work,” he said. “There are other ways to see the mountains and have fun.”

However, another trail that ends (or starts, depending on one’s perspective) in Maine has caught Cannan’s imagination.

“I want to do the Northern Forest Canoe Trail,” he said. The NFCT mainly is a trail of waterways through New York, Vermont, Quebec, New Hampshire, and Maine that ends in Fort Kent where the Fish River meets the St. John River.

His immediate plans, though, are up in the air, Cannan said.

“I am not sure yet. Maybe after the holidays I’ll decide,” he said. “We’ll see. I’ll go back to work and let it sink in,” he said.