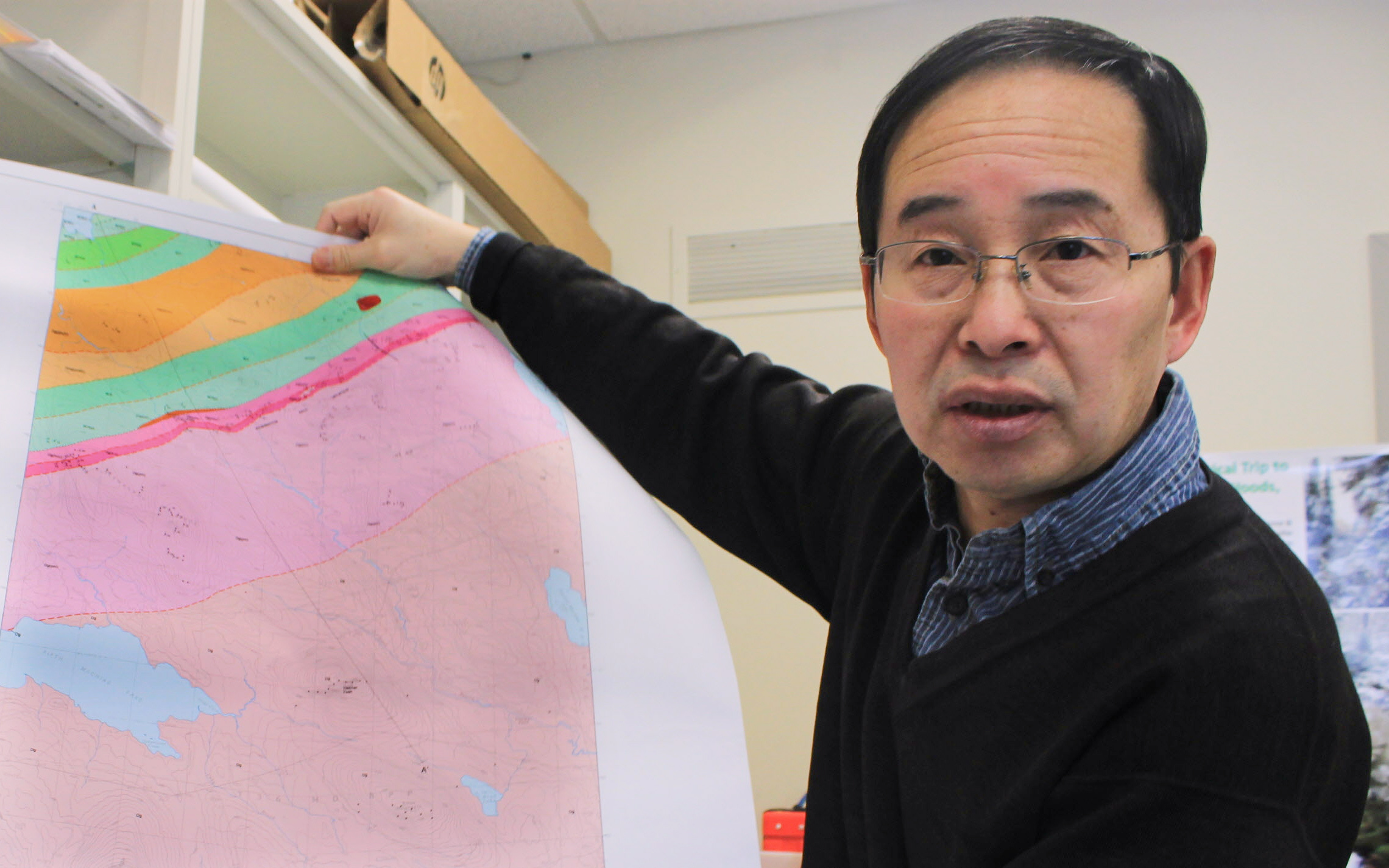

Chunzeng Wang, one of Maine’s most prolific geologists, is the guy many people come to when they need good maps in Aroostook County.

A native of China who turns 55 this month, Wang has spent more than 12 years teaching earth sciences and geographic information systems at the University of Maine at Presque Isle. He took a roundabout path to settling in northern Maine, but is happy with the results.

He grew up in the rural central plains of China and entered the field of geology partly out of a desire to explore nature beyond the flat landscape of his youth.

“I really wanted to see mountains, forests and rivers. Geologists go to mountains because they study rocks.”

He scored well in the highly competitive national college admissions test and enrolled at what is now Guilin University of Technology, then a university focused on earth sciences.

“Guilin is very well known for its beautiful hilly landscape. I just wanted to go far away and thought that’s the perfect place for me to go,” Wang said.

He landed a research job with a professor studying fossils and met his future wife, who grew up in Guilin and worked in the hospitality industry. After graduation in 1989, Wang became an instructor at Guilin, then started graduate school at China University of Geosciences before returning to Guilin to teach.

He went to the University of Colorado at Denver as a visiting professor, where he explored the Rocky Mountains and took summer work as a consulting geologist, logging rock samples on oil drilling sites.

“I went to all the states around Colorado. I wanted to see the country, meet the people and do things exciting,” he said.

In Colorado, Wang met a geologist from the City University of New York, who suggested he work on a research project in Maine and earn a Ph.D. Wang went to New York for his Ph.D., briefly leaving in China his wife and first daughter (now a chemical engineering student at the University of Maine in Orono).

The New York professor was working in Maine on a large, multi-university project mapping the Norumbega fault, the largest fault line in northeastern North America, running from Connecticut northeast to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. He recruited Wang to join the work and they spent part of their summers mapping sections of the fault in Washington County.

Wang officially finished his Ph.D. the day before the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. He investigated positions at several small and large universities, but had his first interview with UMPI and took the job.

“I am not a city person. I didn’t want to work in very populated areas. That’s why I enjoy my work in the North Maine Woods so much,” he said.

Wang has been part of a team researching the geology of the North Maine Woods, parts of which haven’t been charted by geologists since the 1950s. He is probably best known for the community mapping projects he’s overseen with students in the last 12 years, having built UMPI’s geographic information systems program from scratch.

He started to teach GIS and later helped the university land a $100,000 Maine Technology Institute grant to get computers for a dedicated GIS lab. Today, ground-penetrating radar and drone technology allows students and staff to locate unmarked graves and old utility pipes, or create detailed forest surveys.

Wang and his students complete dozens of community-related mapping projects each year, and students often get paid for the work.

“With GIS, the best way for me to teach is for students to be hands on,” Wang said. “I used to go to people and say, do you have any projects? Now, I never go to anybody. It’s always people coming to see me.”

Wang enjoys living in northern Maine while also travelling for research. Almost every summer, he visits family in China and works on China National Science Foundation-supported work on the geologic history of granite mountains in China.

Wang said his hometown in central China, once a rural village, is now a small city of more than 250,000 people. In northern Maine, he said his family has fared well in what is still a rural region, though also much changed over the last 40 years.

“My kids have done well,” he said of his three daughters. “They see Presque Isle as their hometown. They grew up here.”