CARIBOU, Maine — John Kavin of Caribou had no idea that the literal pain in his neck would take him on an adventure across the country, and then to Serbia, in search of a lower risk alternative to proposed surgery.

The 49-year-old began experiencing pain in his neck when he was only 12 years old.

“I would go to my family doctor and complain of swollen glands,” Kavin said recently. “I had this pain in the right part of my throat that would come up every once in awhile without warning. It was like someone took a double edged knife, stuck it down my throat, and wiggled it around.”

A simple massage worked as a short-term solution, making the pain go away for months, but it would always come back. Doctors, at the time, told Kavin’s family that it was just a swollen gland that would subside, or that he was “imagining things.”

Kavin’s brother James, who is 10 years his senior, said he remembers his little brother complaining of the pain as a child.

“It’s been ongoing since he was a kid,” said James Kavin. “He finally got to the point where the pain traveled to his head, and he was in terrible shape, but he tolerated it for several days and it went away again. It was obvious he was in such extreme pain; we were all worried about what he could do.”

Then while extended family and the brothers were visiting their mother for Christmas in 2015, John Kavin experienced the worst pain he’d suffered so far.

“It flared up worse than ever,” John Kavin said. “The pain was in my head and throat, and I couldn’t even open my mouth. It was excruciating.”

With the flare-up occurring on a Friday night, he said he couldn’t schedule an appointment with a doctor for a couple of days, and had to bear the pain until then.

“The doctor took an X-ray and confirmed that it was a salivary stone,” said Kavin, adding that the stone looked “quite large.”

A salivary gland stone is a calcification that forms inside a salivary gland or duct, blocking the flow of saliva to the mouth, according to WebMD. The blockage also can cause saliva to back up into the gland, causing pain and swelling. Inflammation and infection can follow.

Kavin’s doctors told him that a new physician, capable of removing the offending salivary gland, would be coming to The Aroostook Medical Center and that he would be the first one to undergo the surgery, a parotidectomy, at the Presque Isle hospital.

The procedure involves making a large incision in the side of the patient’s neck, exposing a number of highly sensitive nerves that need to be moved aside while doctors remove the gland with the problem. Though modern parotidectomies are somewhat low risk, there is a possibility of facial paralysis.

“You end up with no gland, a facial scar, and risk facial paralysis,” John Kavin said.

While local doctors assured him that the risk of nerve damage was minimal, he was still apprehensive.

Kavin thought there had to be another way and, with six weeks to wait for the scheduled operation, he began researching online for alternatives to the surgery, which local doctors estimated could cost up to $30,000.

He soon found Dr. Ryan Osborne, MD, a world renowned specialist in head and neck oncology, who owns his own LA-based medical institute.

“They have an entire wing dedicated to dealing with tumors and stones,” said Kavin, adding that he was excited to read about what the doctor was capable of doing. “Some of the surgeries he’s done are impossible to imagine.”

“If you look at some of the tumors he’s taken out,” added James Kavin. “Some of them take up the guy’s entire face, but in the after-shot it looks like nothing ever happened.”

Instead of making an incision and delicately holding back sensitive nerves, Osborne’s version of the procedure only requires a small tool, approximately the size of a human hair, that enters the gland and removes the stone piece by piece. The procedure was developed and has been used successfully for more than a decade.

- Doctor Ryan Osborne, M.D., left, founder of the Osborne Head and Neck Institute, poses with his medical team in a Belgrade hospital before performing a Submandibular Sialendoscopy on Caribou resident John Kavin in Serbia. (Courtesy of John Kavin)

Upon learning this, John Kavin said he was immediately sold on the procedure, as it carried no risks of paralysis and he would be able to keep his salivary gland, without which he could endure other issues, including dental problems in the future, he said. Osborne also assured Kavin that the odds of the calcification recurring would be minimal.

“However corny it sounds,” John Kavin said, “their slogan is, ‘You keep your gland. We keep your stone.”

Officials with Osborne’s medical institute, according to Kavin, were “excited” when he reached out, and informed him that he needed to send results from a variety of tests before undergoing surgery. The first of those was a CAT scan that revealed the size of his stone: 17 by 25 centimeters.

“They said I definitely qualified,” Kavin said.

He then was scheduled to undergo the surgery in July of 2015, but decided he couldn’t afford to take the time off. Once again, the pain went away, so he put the procedure off.

The problem did not go away, however.

“In 2017, I went to see my dentist, who I check in with every three months,” Kavin said. “He said, ‘Something’s happened.’ And found six cavities.”

It turned out that the stone, while not causing physical discomfort at that time, was blocking saliva to the lower jaw and having an impact on Kavin’s teeth.

He reached out to Osborne once again and, this time, scheduled a procedure in California for August 2017. He coordinated time off from his business, Countywide Vacuum Services & Sales, and started working on his travel plans.

He also needed a chaperone, since he would still be under the influence of anesthetics when leaving Osborne’s LA facility, meaning his brother James Kavin needed to prepare for the trip as well.

To help with costs, Kavin’s mother suggested that he start a GoFundMe page. The resulting fundraiser, which he called “Pray for The Caribou Vacuum Man,” collected $2,350 in donations.

Kavin, for a brief time, was able to rest easy knowing all his plans were in order. His surgery was scheduled for Halloween. But his final physical before departure, scheduled for Friday the 13th, yielded unlucky results.

“Doctor Osborne himself called my phone literally two days before I was going to leave,” said Kavin. “He said there’s a complication in my medical history and that it can’t be done at his facility, and instead needs to be done inpatient at a hospital.”

The issue was heart-related, as Kavin’s father and grandfather had both died of heart attacks, and Osborne said he couldn’t take the risks associated with anesthetizing him. The surgery could be rescheduled at an LA hospital, but that would be at least four months away, and the cost would balloon to about $80,000 unless he paid $20,000 up front in cash, according to Kavin.

Disappointed, Kavin cancelled his plans just two days before he had been set to leave for LA.

Then Osborne called back the next day, making Kavin an unexpected offer.

“He told me he goes on a mission trip to Belgrade four times a year,” Kavin said, referring to the capital of Serbia in eastern Europe. “At the time, I didn’t know where Belgrade was, but he said he’s going next weekend and that I’d be first on the list.”

After finding out where Belgrade was, carefully considering his options, and discussing the offer at length with his brother, John Kavin decided to fly to Serbia with James for the operation in early November 2017.

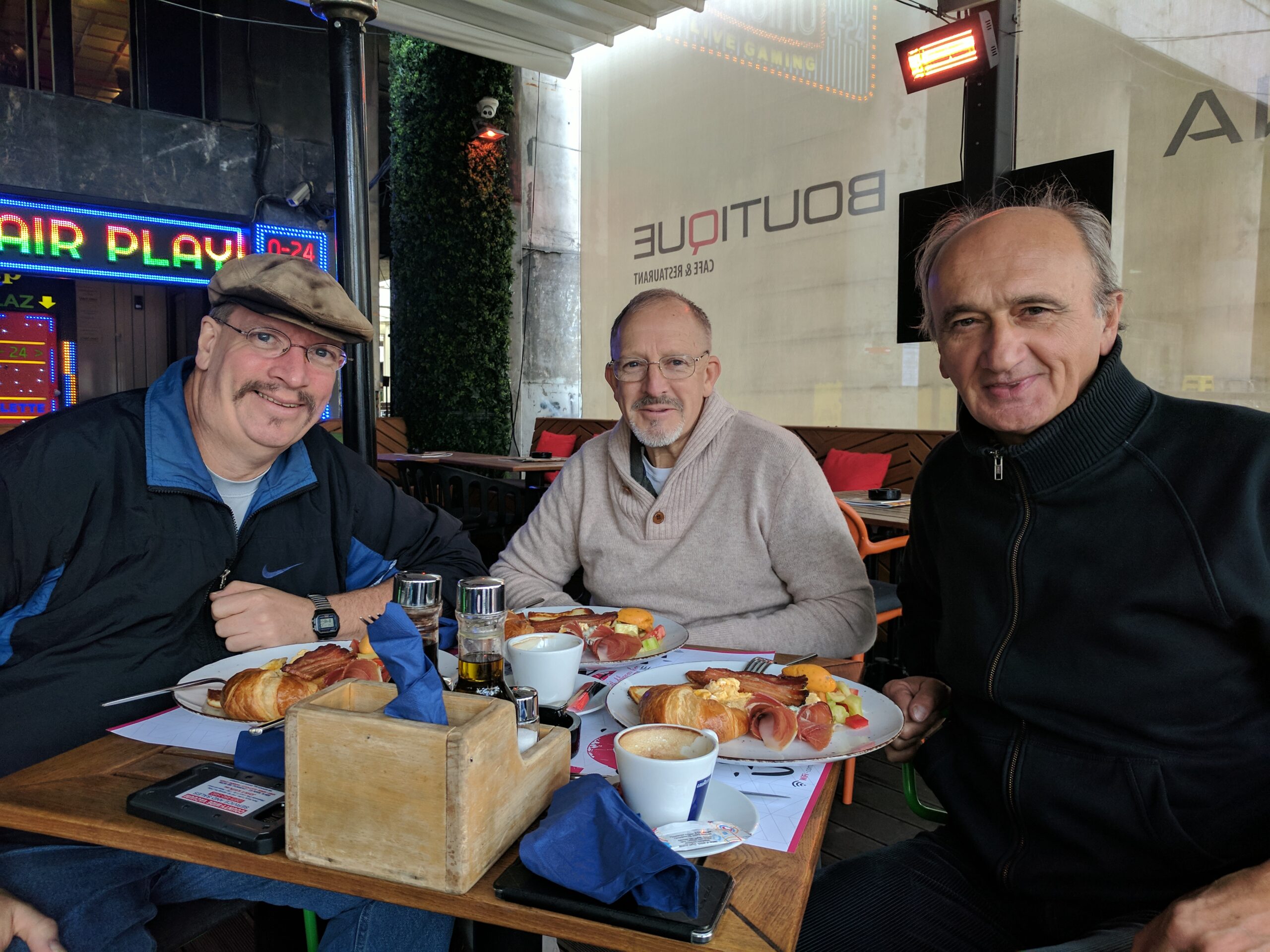

- John Kavin, right, and his brother James of Caribou traveled to Serbia for a less expensive alternative surgery to remove a salivary gland stone. Here, they can be seen sitting together at a local restaurant in Belgrade, the capital of European country shortly after the successful procedure. (Courtesy of John Kavin)

While a trip to Serbia for surgery, on paper, may seem like a far more expensive alternative to a local operation, the donations he had received covered all airfare and lodging for the trip. The surgery itself cost $8,000, much lower than the $30,000 initial estimate for the operation in Maine and less than what it would have cost for the alternative surgery in LA.

Things were looking up as John and James Kavin left for Serbia, but there would be more challenges. After flying from Bangor to New York, the brothers rushed to where the “Air Serbia terminal was supposed to be” only to be told by a security guard that Air Serbia “doesn’t come here.”

“‘Yeah right,’ I told him. ‘I’ve got tickets,’” John Kavin recalled telling the man.

“Nope. It’s not here,” the man told the brothers.

They then approached an official with another airline who called another employee over to look at his screen, and after an intense 15 minutes that seemed to last an eternity, they found the Serbian airline in the system.

“He told me that Air Serbia only comes to New York once or twice a week, and that they, along with Turkey, Mexico, and Ireland, all share one terminal and only come in at a certain time,” Kavin said. “It was like finding a needle in a haystack.”

The Kavin brothers were blessed with a brief respite during the overseas flight, which James said provided first class service for their economy class tickets.

“They had metal silverware and served us wine,” John Kavin recalled smiling.

But within minutes of arrival, the brothers found trouble once again.

John had used Airbnb to reserved Serbian lodging from a host who had a master’s degree in English. However, at the last minute she notified him that she would be in London for the week. Only her mother, who could not speak any English, would be present at the home.

Their cab driver, who apparently knew little English, had trouble finding the location. In addition to communication issues, John’s cell phone did not receive service outside the United States, requiring him to sign into his Airbnb account through his brother’s phone.

After driving down what appeared to be a narrow walkway, and after their Serbian cab driver ominously announced, “This is no place to go,” outside the residence, The Kavin brothers met their host’s mother, who “would only talk louder” in an effort to bridge the communication gap.

Despite being severely jetlagged, the brothers used James’ phone — it could only get a signal in an absurdly specific spot at the kitchen table — and with the help of a translation app, logged into John’s Airbnb account, and found another lodging with an English speaking host.

From there, the brothers’ luck began to change. Kavin met Osborne at a Belgrade hospital, had a successful surgery and, because Air Serbia only travels to America once a week, was able to spend several days taking in the sights of a foreign country.

James said they befriended an English-speaking cab driver named “Bobby,” who they paid $25 to take them on a Serbian tour.

“He was happy to converse,” said James. “He said it was a good opportunity to refine and practice his English. On our last day, we hired him to take us to the places that would be of interest to locals, not just the normal tourist spots.”

“We wanted to see the stuff only a local would know about,” said John.

Bobby had apparently lived through three different regimes, and told the brothers a great deal about Serbian history from his perspective, which prompted an engaging conversation in which the brothers kept asking questions about the country.

They also befriended a Turkish archaeologist, who showed them a fort that James said had been occupied “by some military force since 800 B.C.”

John and James Kavin returned to the states without any issues and while their adventure was unforgettable, John is mostly relieved to no longer be plagued by the stone.

“The best part,” he said, “is that I know, without a doubt, that it’s not coming back.”