PRESQUE ISLE, Maine — For around 15 years Richard “Dick” Graves, optometrist and local historian, has been the “keeper” of his family’s old photographs, letters and keepsakes, preserving their story in hopes that one day future generations will continue passing down the history.

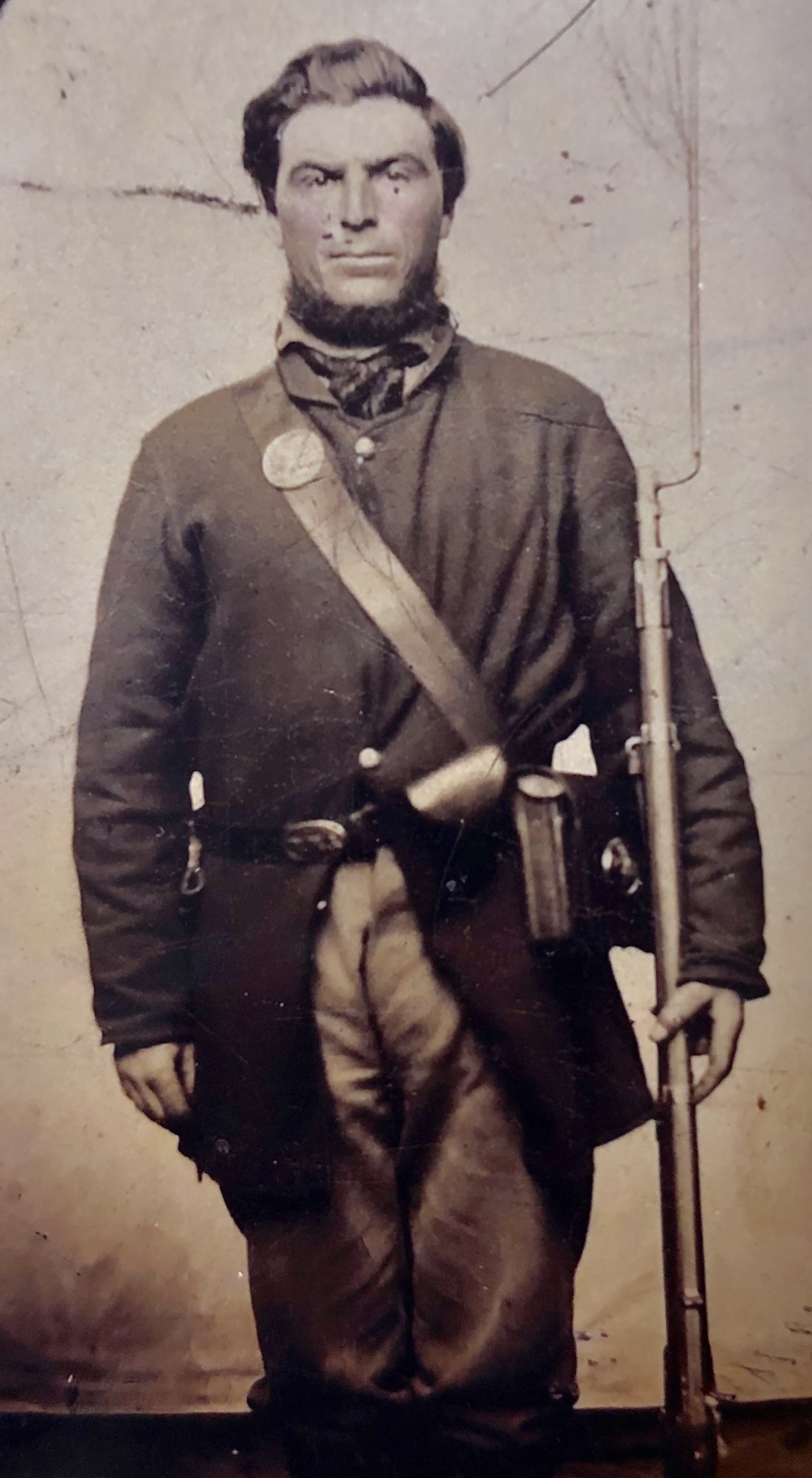

But it was not until recently that a relative — one Graves didn’t even know he had — gave him a rare and one of his most treasured family items: a Civil War-era tintype photograph of his great-great grandfather, Alexander Graves.

Kristina Martin, of Boston, had begun researching her family’s history and found out that she and Graves are second cousins. His father — Richard Alexander Graves II — was a first cousin of Martin’s father. Martin visited Graves this past summer and before she left she handed him the tintype photograph, which she said had been passed down in her family along with some old letters.

“It’s extremely rare for anyone to find a tintype photograph from their own family,” Graves said.

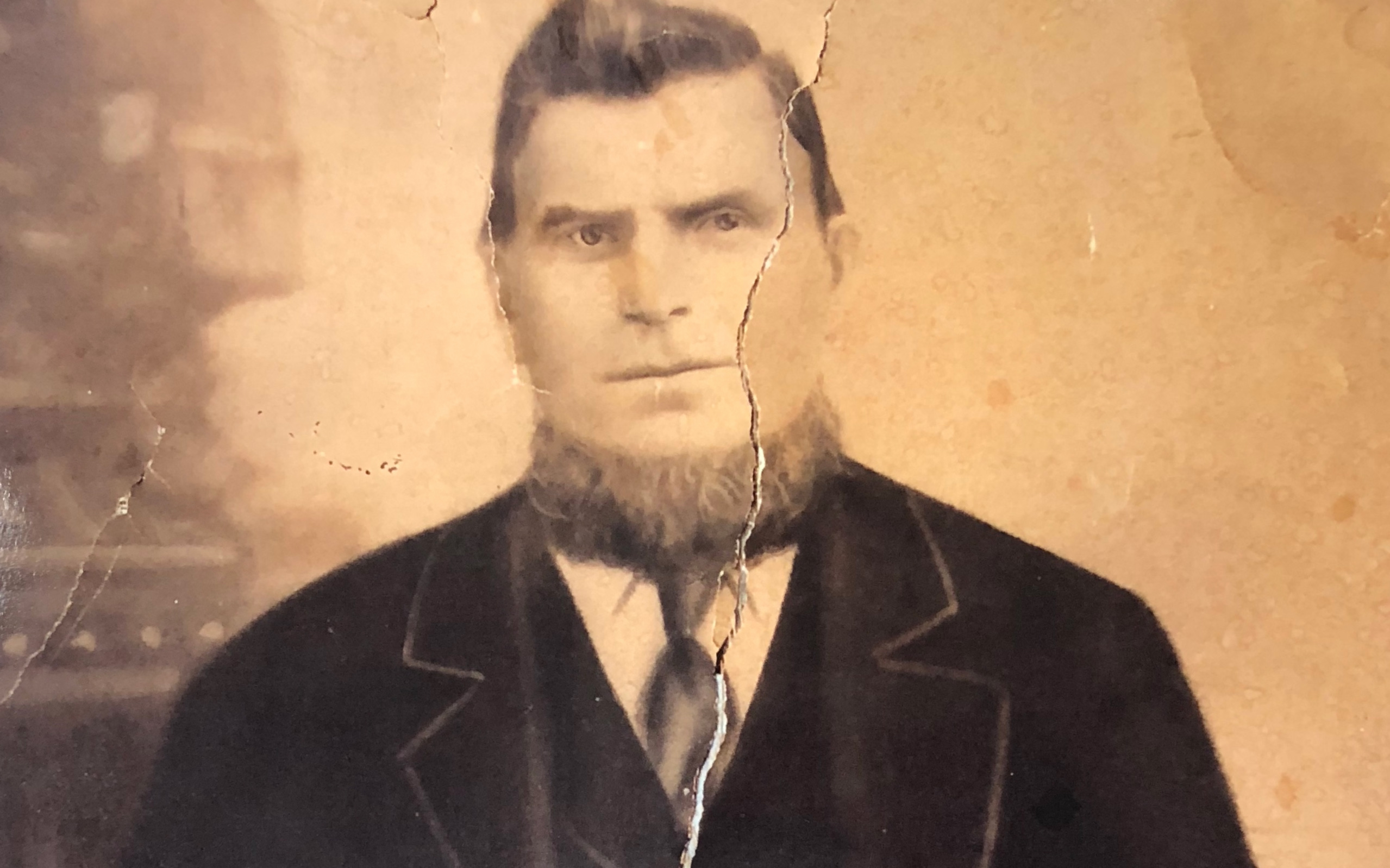

Richard “Dick” Graves of Presque Isle recently received this rare 1864 tintype photo of his great-great-grandfather, Alexander Graves, from Kristina Martin, whom he found out is a second cousin of his. Dick Graves has been researching and collecting his family’s old photographs, letters and other keepsakes for around 15 years and has published several books about Presque Isle history. (Courtesy of Dick Graves)

Martin did not know who the man in the tintype photo was, but Graves compared the tintype to a larger 1885-dated photo he has of Alexander Graves and found that the two men were the same person. He knew the photo was a special gift because during the Civil War era, tintypes were the only form of photography that the military had to capture images of soldiers before they went into battle.

Tintype photography was patented in 1856 just prior to the Civil War, according to Collectors Weekly. The name comes from the words “melainotype,” which refers to the “dark color of the unexposed photographic plate” and “ferrotype,” which indicates the plate’s iron composition.

Photographers would produce an underexposed negative image onto the thin iron plate and blacken the plate by painting, which darkened the background and made the photograph look like a positive image. Civil War-era photographers often shot tintypes against a painted backdrop inside a studio and the medium remained popular through the 1930s and into the 1940s.

Alexander Graves’ tintype photograph was taken in 1864, after the 26-year-old had enlisted in the 15th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment. After being wounded in battle, he was discharged and returned to his hometown in New Brunswick, Canada. Graves is unsure why his great-great-grandfather and his new wife settled in Presque Isle in 1866, but knows that they raised six children.

One of those children — Graves’ great-grandfather Richard Graves — settled on Dudley Street in Presque Isle in 1888 or 1889 and raised five children, three boys and three girls. Ike Graves worked in the hardware business and also established Graves’ Funeral Home in 1939, which still exists today in Presque Isle, Caribou and Mars Hill as Duncan-Graves Funeral Home. Earl Graves opened a pharmacy and Richard Alexander Graves — Graves’ grandfather — practiced medicine from 1912 until his death in 1945 at age 55. Alexander Graves died in Presque Isle in 1901.

The name Richard Alexander Graves is one that has been passed down not only to Graves’ father and himself, but also to his son and grandson, who are fourth and fifth generations with that name.

“Not too many families carry on their names anymore,” Graves said.

Graves is no stranger to documenting the history of some of the most unique people and places of Presque Isle. In 2006 he published his first book of historic photographs and stories, “Forgotten Times: Presque Isle’s First 150 Years,” with help from Kimberly Sebold and her local history students at the University of Maine at Presque Isle. He followed that book with “Forgotten Times: A Walk Through History” in 2007 and “The History of Public Education in Presque Isle, Maine 1837-2012” in 2012. That third book is still available through the SAD 1 superintendent’s office.

Through the years Graves has been a careful documentor of family and local history, scanning all old photos and documents into his computer for preservation. He hopes his isn’t the last generation who will appreciate hearing stories of Presque Isle’s past.

“I enjoy doing the research and it’s important to me because very few people collect this history anymore,” Graves said. “I have three children who’ll inherit these photos and I hope that they’ll want to have them, too.”