LIMESTONE, Maine — In just two years, middle school students at Limestone Community School have gone ice fishing, downhill skiing, camping, canoeing, hiking, horseback riding and snowshoeing, grown vegetables and made their own maple syrup.

By the end of this school year, they want to start a school garden and farmstand and learn how to cross country ski on local trails. It’s all thanks to a post-COVID movement that’s driving schools to keep children more engaged and less hooked to screens.

As social distancing and online learning increased during the pandemic, so did mental health struggles among Maine students. Teachers saw more signs of anxiety, sadness, boredom and disengagement, which coincided with troubling statewide data that backed their concern. While combating these issues, teachers have found that being outdoors makes students less stressed and more willing to stay in school.

Outdoor learning is not entirely new to rural Maine counties, known for their undisturbed nature trails, waterways and snowmobile and ATV cultures. In Washington County, East Grand teachers launched an outdoor program 20 years ago, which remains popular. But social media and pandemic isolation did not exist two decades ago, and now more teachers are finding innovative ways to engage students.

Similar outdoor experiences are being offered in Caribou and Van Buren schools. Limestone teacher Caroline Reed turned her gaze outward when she saw many students struggle to learn during the COVID years.

“There was a lack of motivation. Some students weren’t completing their work and we saw more behavioral issues. They almost didn’t see the point of going to school anymore,” said Reed, who teaches seventh and eighth grade math and science. “We wanted to reignite their desire to be here.”

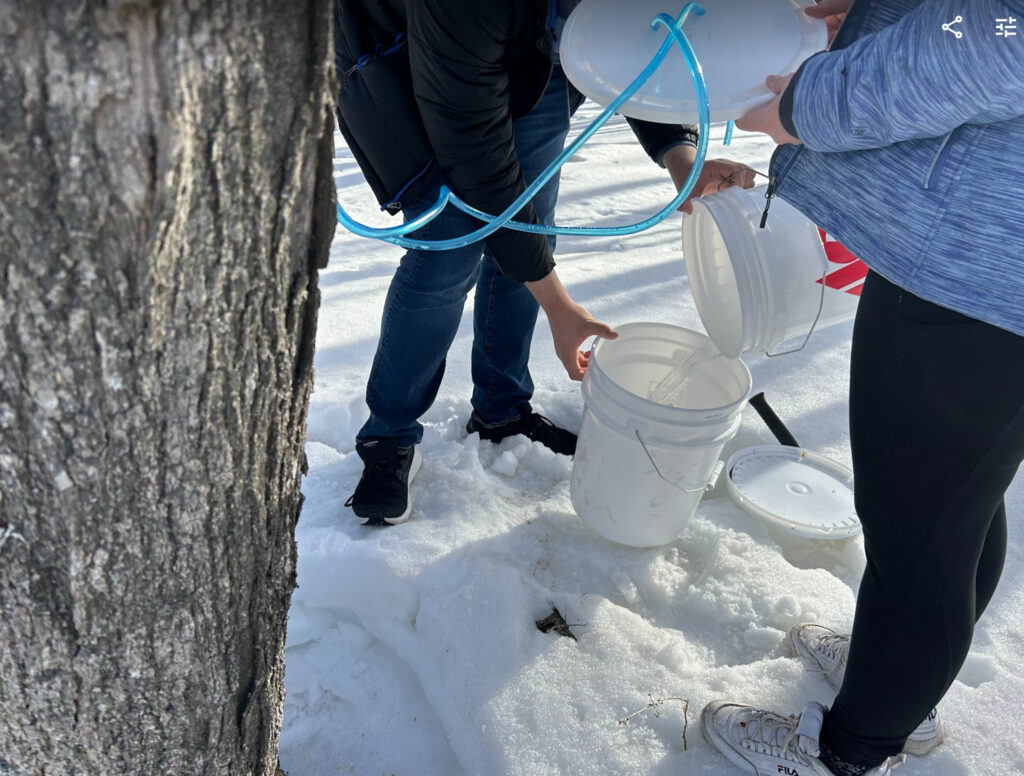

Along with former colleague Hogan Marquis, who taught fifth and sixth grade math and science, Reed started an annual ice fishing trip to Madawaska Lake, camping trips and spring maple syrup tapping in 2021.

One year later, Marquis and Reed launched the school’s first formal outdoor club with $250,000 from the Maine Department of Education’s Rethinking Responsive Education Ventures, which is funded through $16.9 million in federal COVID relief monies. Forty five school districts have received funding from that program since 2021.

The Maine DOE funds helped Marquis and Reed purchase a dozen canoes and fishing and camping gear. A $1,500 mini grant from the Maine Environmental Education Association allowed them to purchase bog boots and weather-proof jackets.

With $100,000 of DOE funds left, the teachers want to purchase cross-country skis and materials for starting a school garden. The school is repairing a former bus garage to use as storage space.

Outdoor experiences, like learning to downhill ski at Quoggy Jo Ski Center in Presque Isle, have helped students gain new skills, forge stronger relationships with each other and perform better in school, Reed said.

“A lot of students started off very fearful [of skiing] but by the end of the six weeks, they were flying down the mountain,” Reed said. “We’ve seen students ask more questions in class, give answers and help each other out.”

Many school districts have tapped into pandemic relief funds or used special grant monies to give their students learning and bonding experiences beyond the classroom. Some have started outdoor programs, while others are adding more everyday lessons to their curriculum, said Marcus Mrowka, Maine DOE communications director.

“I once went into a third grade class in Portland where the teacher showed photos of plants and then the students went outside the school to look for them,” Mrowka said. “These are small activities students can do to learn about their natural environment.”

That’s exactly what Caribou Community School teacher Vaughn Martin had in mind when he created an outdoor learning garden on school property last year. In the midst of COVID, Martin began taking his fifth grade students outside more so they could take breaks from wearing masks.

Today, the garden features stone and brick pathways, plant species, biome replicas, a weather station and bird feeders. Weather permitting, students head to the garden daily to identify insects and plants, track weather patterns or take part in other nature-based lessons. Teachers often hold classes inside a new gazebo, which the school district funded through Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Funds.

Students are already more engaged outdoors, Martin said. Unlike reading a textbook or discussing topics in class, students can touch, feel, smell and get excited about the nature around them.

“I think being outdoors is better because in a classroom we might get bored and not learn as well,” said fifth grader Mykala Shaw. “I focus more outside.”

Van Buren science teachers Laurie Spooner and David Barbosa used a $1,500 mini grant from the Maine Environmental Education Association to purchase maple syrup tapping equipment and binoculars for bird watching.

In March, Spooner led a group of sophomores, juniors and seniors outdoors to tap trees on a local resident’s property. Students evaporated maple tree sap with a boiler that a machinery class built. Spooner and colleagues already plan to continue the maple project next year and think of other outdoor ideas.

“We wanted students to realize the wonderful resources they have in their backyards,” Spooner said. “It’s such a different environment than a traditional classroom.”