LIMESTONE, Maine – The Loring Air Museum wants to preserve a historic part of the Air Force base, but its goal conflicts with the state-funded economic agency that owns most of the former military facility and wants to redevelop it.

Created by the Legislature in 1993, the Loring Development Authority still owns and maintains most of the former Loring Air Force Base, which closed in 1994. The authority developed the 3,800-acre Loring Commerce Center as an industrial, commercial and aviation park, but has struggled to retain larger companies.

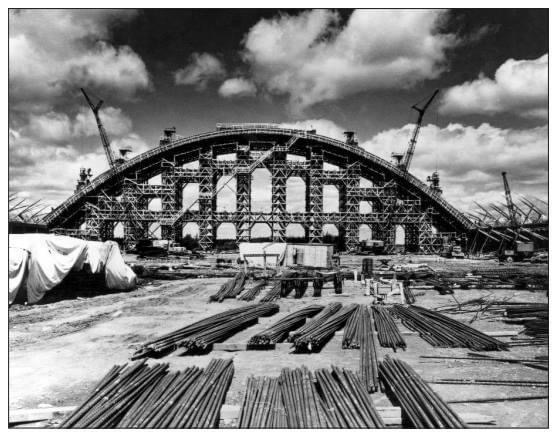

The authority owns Loring’s 1,600-acre airport, including the “Arch Hangar,” a 340-foot wide by 314-foot long structure that is 90 feet tall in the middle. It once housed B-36 bomber aircraft and stored nuclear arsenal materials at the height of the Cold War.

A proposed legislative bill, LD 1998, would transfer ownership of the hangar to the Loring Air Museum, which has operated at Cupp Road on the Commerce Center since 2005. Museum volunteers want to expand their current exhibition space and preserve what they see as a crucial part of local and United States history.

The battle for who gets the hangar will play out in Augusta beginning Tuesday with a public hearing on the bill.

The hangar’s two-year construction from 1947 to 1949 became an “engineering marvel,” said longtime museum volunteer Cuppy Johndro of Caribou.

“When it was built, there was a continuous, 26-hour pour of cement onto 12 individual sections of roof so there wouldn’t be any cracks. There are no seams today,” Johndro said.

Though the U.S. government intended to build more arch-style hangars at Air Force bases, the costs of fighting in World War II and the Korean War ended most projects. The only other remaining arch hangar today is at the Ellsworth Air Force Base in Rapid City, South Dakota, Johndro said.

Currently, the 2,500-square-foot Loring Air Museum includes thousands of photographs and memorabilia from Loring’s Air Force days. If the museum relocated to the hangar, volunteers would want to acquire B-52 and KC-135 aircraft that would need to be displayed indoors due to northern Maine’s harsh winters, Johndro said.

Museum volunteers have hosted numerous tours inside the hangar for local students and tourists, but owning the building would give the volunteers their own key, which they currently do not have, Johndro noted.

In 2015, museum volunteers started the process of having the arch hangar become a historic monument under the National Register of Historic Places, but they ceased those efforts out of respect for Loring Development Authority’s hopes to revitalize the airport.

With LD 1998, the museum is hoping that the Legislature transfers the hangar to it, given that no major redevelopment of the structure has ever occurred.

“I understand where [the Loring Development Authority] is coming from, but it’s been eight years and nothing has been done with the hangar,” Johndro said. “They’ve had 30 years since the base closed to do something but nothing truly lasting has happened.”

Starting in the mid-2000s, the departure of companies like Sitel and Maine Military Authority have led to hundreds of local jobs being lost, prompting the authority to seek other redevelopment avenues.

Loring Development Authority needs to maintain ownership of the arch hangar in order for the Federal Aviation Administration to switch the airport’s designation from private to public, said Jonathan Judkins, the authority’s interim president and CEO.

Judkins declined to comment on the proposed legislation that would transfer the hangar to the museum.

Since 1997, the Loring Airfield has operated as a private airport, with pilots needing permission before landing. Though various aviation and aerospace companies, most recently Brunswick-based bluShift Aerospace, have launched aircraft from Loring’s runways, no company has made the airport its permanent home.

The authority is working on an airport master plan that will include strategies for recruiting companies, specifically those looking to test and develop unmanned aircraft systems, low-orbit space systems and technologies to detect drones and avoid aircraft collisions. Last year, Portland, Maine-based company HyperSpace announced plans to assemble and test a low-orbit, rocket-powered “spaceplane” at Loring’s airport.

In addition to the arch hangar, the Loring Airfield includes two 12,100-foot runways, a 38,000-square-foot former jet engine repair facility, control tower and lighting vault and three other hangars that are 194,000, 41,000 and 22,000 square feet, all of which date back to the base’s original construction in the 1940s and ‘50s.

Any transfer of ownership of the arch hangar would not affect future projects at Loring, including DG Fuels’ anticipated $4 billion sustainable aviation fuel production facility.

Though the Portland-based investors Green 4 Maine own 450 acres of Loring now, their land does not include the airport.

The Maine Legislature’s Committee on Innovation, Development, Economic Advancement and Business will hold a public hearing for LD 1998 Tuesday, Jan. 16 at 1 p.m. in Augusta to receive comments about the proposed bill, which is sponsored by Sen. Troy Jackson, D-Allagash.

Jackson was not immediately available for comment Friday.

This story was updated to remove the reference to B-52 and KC-135 aircraft as fighter jets. The B-52 is a bomber and the KC-135 is a refueling tanker.