PRESQUE ISLE, Maine — Denise Bosse has worked in special education for more than 40 years and says it’s never been harder to be a special ed teacher.

“Special ed is in a rough place,” said Bosse, director of special education services at School Administrative District 1 and a long-time teacher in Caribou schools. Between the demands of teaching children with a range of disabilities and the associated administrative work, special education is one of the hardest fields in education, Bosse said.

“If special ed teachers could just work with the students and the families, I think we would have ample special ed teachers.”

In many Maine school districts, special education services have grown in recent years, as more children start school with a spectrum of mild to severe learning challenges that may also be related to difficult life circumstances, she said.

“Children can suffer from PTSD just like adults can suffer from PTSD,” Bosse said, referring to post-traumatic stress disorder. “The drug problem recently has had a huge impact on families.”

Bosse said she has seen the special education field change drastically since she started teaching in Maine in the 1970s.

She grew up in Syracuse, New York, and said she went to the University of Maine Orono because New York state universities had capped enrollment during a budget crisis in the 1970s. Her father also hailed from coastal Maine.

“I thought I would go to UMO for one semester, and go back to New York when the admissions opened in New York again. I got to Orono, made friends, joined organizations and met my husband, a County boy.”

When she first started teaching in the 1970s, most special ed students were those with moderate and severe intellectual disabilities. Since then, the special education field has become “broader and broader,” based on federal and state defined-conditions that encompass learning disabilities, depression and mental health conditions, autism spectrum disorders and other medically-defined conditions such as attention deficit and hyperactivity.

Many students with learning disabilities may have struggles with reading, math, or both.

“They can learn to read, it’s just that as a special education teacher you are trained how to approach it,” Bosse said.

Those disabilities often can overlap with behavioral and emotional problems that may stem from aspects of a student’s personal lives and end up impacting their overall education.

“Some students can hold their act together in the classroom, but then they come to the resource room and they feel they can act like themselves and then let everything out,” Bosse said. “Special ed teachers almost need a degree in social work or counseling.”

Bosse said many special ed teachers are dedicated and doing their best to meet the needs of their students.

Special ed teachers often work with students over their entire academic career in a school and develop annual, personalized education plans for each student. They also meet with families at least once a year.

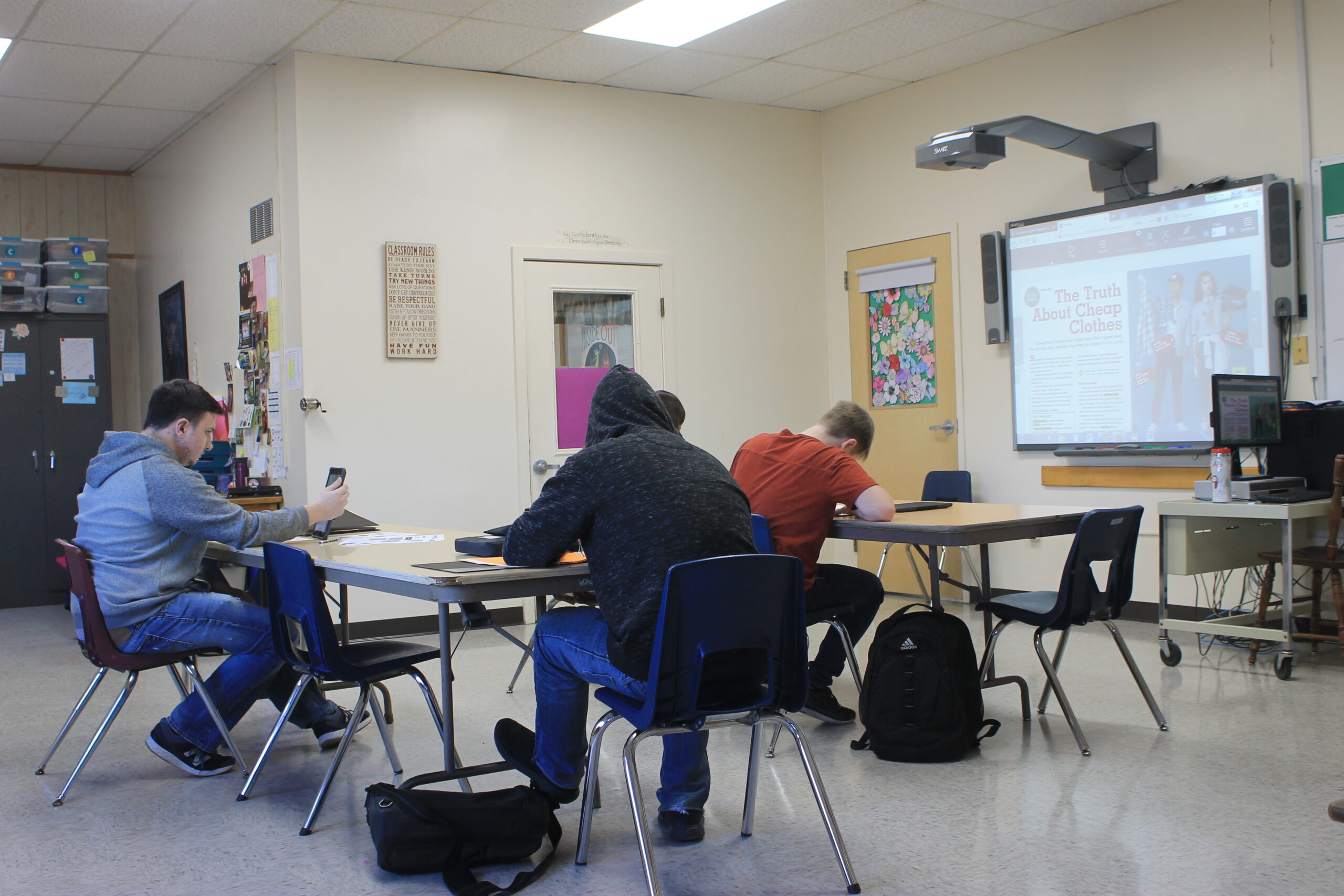

The goal of special education, and a requirement under federal law, is to offer students the “least restrictive environment,” or “to actually keep special education students in the traditional classroom with their peers,” Bosse said.

That can mean a whole range of special instruction support, programming or accommodations for special ed students, depending on their needs, Bosse said.

“A student that has ADHD, in order for them to be with their peers when it’s silent reading time, they may be allowed to take their book and walk back and forth in the back of the class while they’re reading, because they need to have that movement activity so they can focus.”

Other students have a special ed teacher or technician in the regular classroom with them for certain subjects, offering individualized support.

With these changing regulations and increasing numbers of special education students and services have come additional costs.

Across the state between 2006 and 2013, per-student special ed costs increased 37 percent, while spending for regular instruction increased 17 percent, according to the University of Maine College of Education. Sixteen percent of public school students in Maine received special ed services in the 2013-2014 school year, compared to 12 percent nationwide, according to the National Center for Learning Disabilities.

In SAD1, 18 percent of the district’s approximately 1,800 students receive special ed services, according to Bosse. In the 2015-2016 school year, special ed services in the Presque Isle area school district cost $2.79 million, compared to $8.3 million for regular instruction cost. In Maine, the state government contributes to the cost of special education by paying all districts the equivalent of 30 percent of the district’s’ previous year’s special ed costs.

Many school districts have seen more students receiving special education, often in tandem with increases in childhood poverty, said Roger Shaw, superintendent of the Easton School System, where 21 percent of students receive special ed services.

Easton schools have received kudos from the likes of Time Magazine for “beating the odds” with a 96 percent graduation rate and 92 percent college placement rate. The district has seen an increase in childhood poverty and special education needs in recent years, along with the associated costs, Shaw said. Forty-one percent of Easton students come from lower-income households and qualify for free or reduced price meals.

“It’s more costly to educate kids out of poverty than out of affluence,” Shaw said in an interview last year.

For special ed teachers, the largest challenge in their profession is often the administrative bureaucracy associated with teaching, Bosse said, estimating that paperwork and record keeping can take up a quarter to a third of a teacher’s time.

Past federal and state initiatives to reduce paperwork have fallen flat, but significant reform is needed if university education programs and K-12 schools are going to be able to attract new special ed teachers to the field to meet the student need.

“If I want to be a good special ed teacher, I have to give up other aspects of my life,” Bosse said.

“You end up coming to school early, staying late and taking work with you home at night and giving up a lot of weekend time.”