As part of Southern Aroostook Soil and Water Conservation District’s Winter Agricultural School this year, we held a class with Maine Forest Service’s Nate Siegert, an expert on the invasive forest pest emerald ash borer.

During his presentation, Siegert indicated that while EAB affects all species of ash trees, a preferred host is the brown ash. Since brown ash, also called black ash, is an important cultural tree to the Wabanaki peoples, I began wondering how EAB’s detection in Maine might affect those whose culture, identity, and economics it is interwoven with.

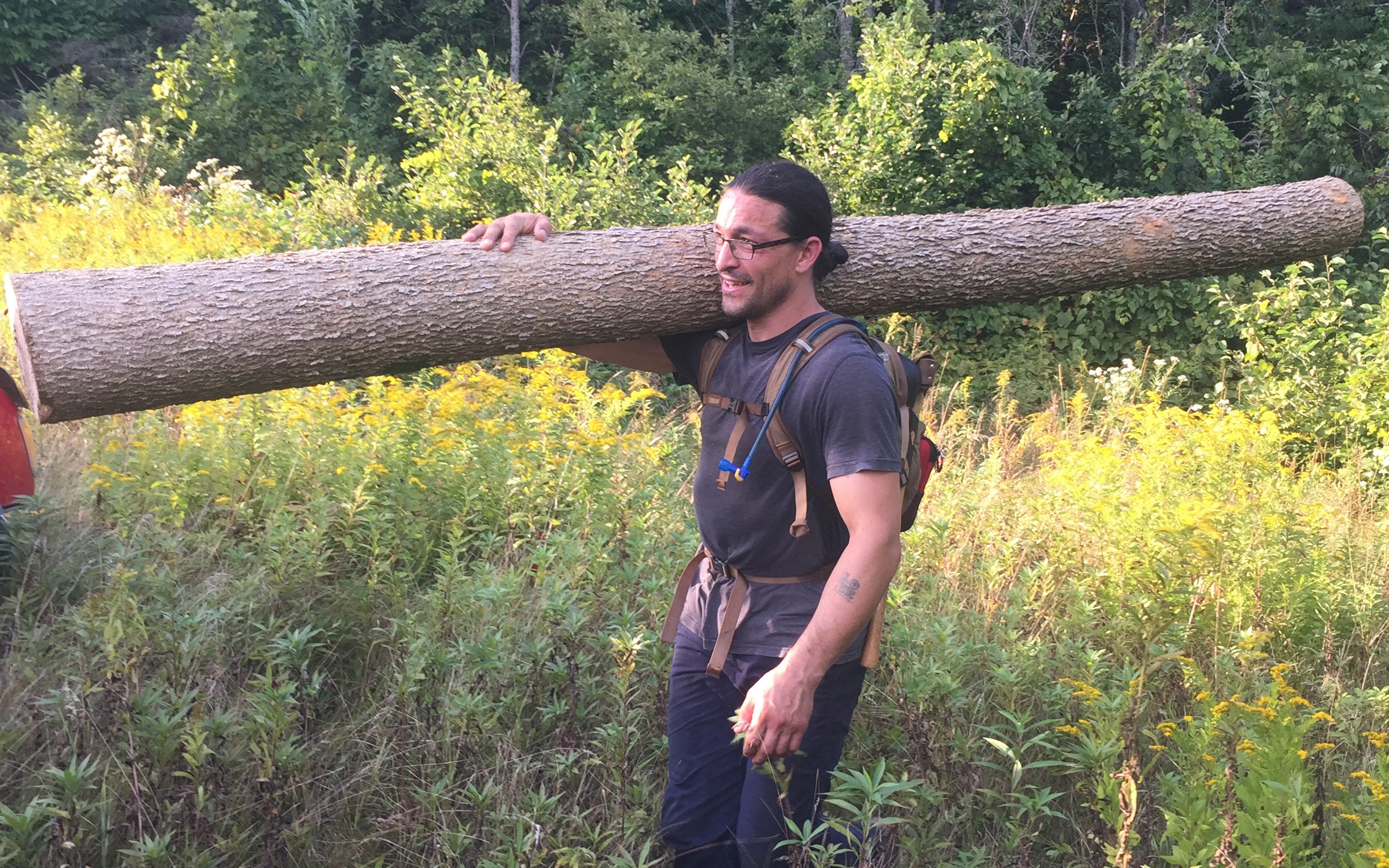

One person whose basketmaking is inseparable from his identity is Passamaquoddy tribal member Gabriel Frey, a 13th generation basketmaker. Frey learned how to make baskets from his grandfather, Fred Moore, who encouraged him to find his own voice within the art. He continues to use the same techniques as his ancestors to turn brown ash trees into functional and beautiful baskets, each step of the process done by hand.

Passamaquoddy tribal member Gabriel Frey, a 13th generation basket maker, carries a brown ash log to be use for basket weaving.

(Contributed photo)

Frey’s wife, Suzanne Greenlaw, is a Maliseet who grew up in Oakfield and is currently a doctoral student at UMaine. Her research project’s focus is to develop a model to inventory and assess high quality brown ash stands within Maine and begin a management plan in the face of EAB’s arrival.

Through her research and Frey’s basketmaking, she understands the economic and spiritual connection of the art and how that hinges on the potential of the ash trees demise. Yet, she remains optimistic and believes that science and knowledge will help provide tools to target and manage basket quality ash stands in the future. Frey acknowledges the possibility of one day no longer being able to make baskets but for now, he is also hopeful that current research will find a solution.

Within southern Aroostook, Micmac basketmaker Richard Silliboy continues making baskets with the same time-honored traditions. Growing up, Silliboy helped his mother as she weaved 10 dozen baskets a week, making .50 per basket. Silliboy makes those same “potato picking” style baskets now and sells them at prices that better reflect the craftsmanship and work of each.

Baskets have always had functional purposes and that hasn’t changed. As Frey’s grandfather encouraged him to bring his voice to his baskets, Silliboy’s mother had her own voice and to this day, coming across a basket at a yard sale, Silliboy can tell if it is one his mother made.

Silliboy has been active in working with people like Siegert and other tribal members from EAB infested states in providing education about EAB. Again, when asked about the impact EAB could have on the Wabanaki peoples culture and livelihood, Silliboy remained hopeful. He is more concerned about the loss of basketmaking knowledge within the Micmac culture and how that will affect that deep connection they have with the brown ash.

And perhaps there is cause to hope. Siegert is coordinating with several tribal, state, federal and university partners to conduct ecological and sociological research on brown ash, EAB impacts, and management. The goal is to take the knowledge gained to better moderate impacts in areas like Maine. He hopes that they will be able to monitor the EAB infestations in an effective way and reduce the spread of EAB to new areas, while also having a plan in place for when EAB becomes established in valuable brown ash stands.

For the Wabanaki peoples, implementing management tools may enable the brown ash to remain an integral part of their culture for years to come.