PRESQUE ISLE, Maine — For many people in Aroostook County, suicide is a topic that is both hard to talk about and one that hits close to home. A recent training held at the Boys and Girls Club of Presque Isle encouraged community members to go beyond the statistics and think of how they could potentially help someone in need of support.

“One of the biggest misperceptions is that if we talk about suicide we’ll put suicide in someone’s mind,” said Cory Tilley, project coordinator for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, or SAMHSA, program at the Boys and Girls Club.

As part of grants provided by SAMHSA’s Native Connections program and the Methamphetamine and Suicide Prevention Initiative, Tilley has held many suicide prevention and mental health first aid trainings to benefit people both in the Aroostook Band of Micmacs and the surrounding community.

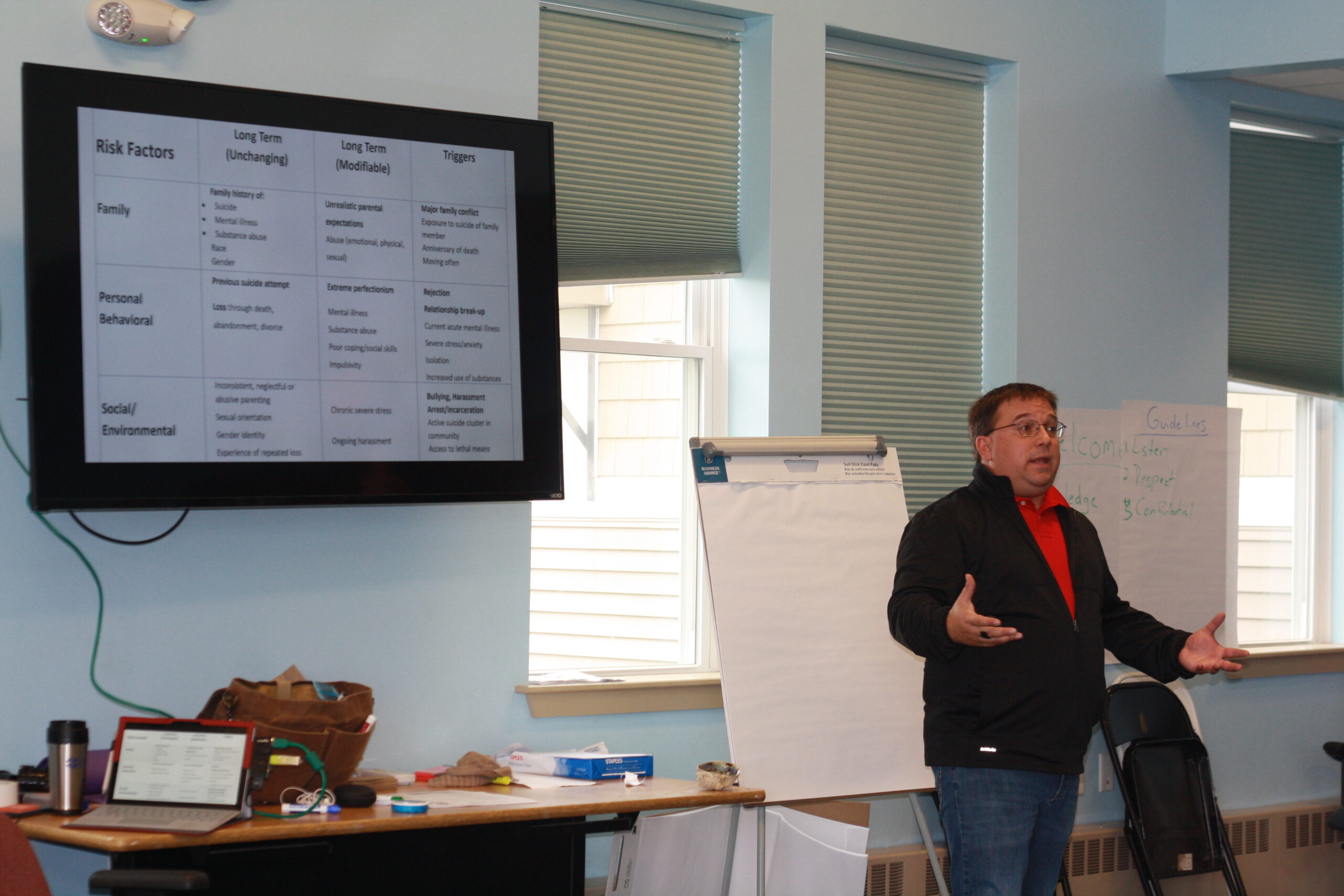

On Monday, Sept. 16, Tilley hosted the first of two suicide prevention trainings, in honor of National Suicide Prevention Month in September, which covered topics such as risk factors for suicide, how to connect with someone who might be having suicidal thoughts and state and local mental health resources.

According to the latest statistics from the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention, suicide is the second leading cause of death among Maine youth ages 10 to 24 and the fourth leading cause of death among youth ages 10 to 14. Those in Native populations are 15 percent more likely to attempt suicide due to factors such as cultural distress and generational trauma.

Tilley also noted one statistic that proved surprising for many people in attendance.

“Even though New England has the lowest overall rate of deaths by suicide, Maine has the highest rate of those deaths in the U.S.,” Tilley said. “Two-hundred seventy-seven people on average die by suicide each year in Maine.”

The Maine CDC states that Maine’s suicide rate is 19.3 percent while the national average is 14.8 percent.

But Tilley did not want to simply list statistics. He also wanted to promote change in how many people tend to talk about suicide. He explained that instead of saying that a person “committed suicide,” the preferred, and more accurate, phrases to use, are “died by suicide” or “died of suicide.”

Tilley explained that the word “committed” promotes misunderstanding about the ways in which a person’s brain functions when contemplating suicide.

“They have not committed to the idea,” he said. “They’re actually ambivalent about doing it, but they want you to ask them in a specific way.”

To elaborate on his point, Tilley told the story of a former colleague with whom he had lost touch for two years before seeing a Facebook message from him. In the message the colleague wrote, “Can’t do this anymore.” After initial confusion, Tilley asked the colleague, who had since moved to Vermont, if he was thinking of suicide and if he had a plan.

The colleague admitted that he planned to drown himself.

After calling Vermont law enforcement, Tilley later learned that the colleague had been found in a nearby pond and was recovering in a hospital.

“When I connected with this person later, he said ‘Thank you. I knew you would know what to do,’” Tilley said. “No one else in his life had acknowledged directly what he was going through.”

There are simple but profound statements, Tilley noted, that can help people connect with someone who might be going through deep emotional pain. Instead of saying, “I’m concerned about how you’ve been acting lately,” focus on the person, not their behavior, and say, “I’m concerned about you … about how you feel” or “You mean a lot to me and I want to help.”

When the time comes to bring up the subject of suicide, phrases that can help someone be direct but not in a confrontational or judgmental way are, “Are you thinking about suicide?” or “How long have you been thinking about suicide?” If a person admits to thinking about suicide, Tilley said, asking them if they have a plan often leads to them admitting whether or not they do.

The next step is to say something like, “You’re not alone. Let me help you” or “I know who you can take to” and lead the person to someone who can help.

“The idea that ‘suicide is a choice’ is a misperception. In fear mode, the person is only thinking about getting rid of this unbearable pain. The majority people who have survived suicide have said that in the moment it was happening they did not want to die,” Tilley said. “It was a cry for help.”

Potential risk factors for suicide could include depression, a family history of emotional trauma or stress, post traumatic stress disorder, lack of access to healthcare or mental health resources and unsafe home environments.

Warning signs of suicide might include expressing hopelessness about the future, displaying severe emotional pain or distress, withdrawal from family or close friends, extreme changes in mood or behavior or sleep patterns and giving away personal possessions.

Melanie Greaves was one of 10 people who attended the suicide prevention training on Monday. She noted that as the site coordinator for the Boys and Girls Club’s 21st Century After School Program being aware of risk factors for suicide can help her respond better if she encounters someone in crisis.

“It’s helpful to know what language we should use to let someone know we’re there for them,” Greaves said.

Jolene Brecht, a teacher’s aide for 21st Century After School Program, also said that the training opened her eyes to how prevalent the issue of suicide is and how people can help others.

“It’s the hardest question to ask someone, but it’s one that we need to ask,” Brecht said.

To reach a suicide prevention hotline, call 888-568-1112 or 800-273-TALK (8255), or visit www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org.