Maine saw its first death from influenza late last month, after an older resident of Hancock County died during the second to last week of 2018.

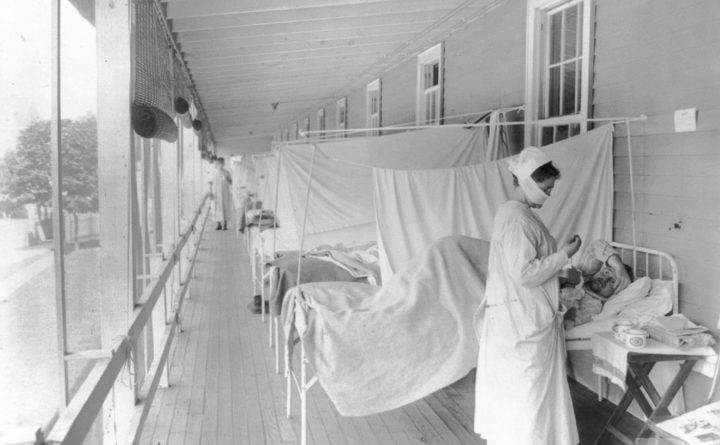

However, 100 years ago, Maine saw thousands of flu deaths, and millions more died all over the world, during the 1918-19 flu pandemic (the “Spanish flu”) that killed an estimated three to five percent of the world’s population, or between 50 million and 100 million people.

The only other epidemic comparable in scope is the Black Death, which occurred in Europe in the 14th century — but which took more than 20 years to accomplish what the Spanish flu did in less than a year.

A Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention timeline of the major developments during the epidemic in Maine in 1918 and 1919 offers a historical perspective as well as a chance to learn from society’s mistakes in handling the situation 100 years ago.

Though the pandemic first reached the U.S. in January 1918, it was a second, more virulent strain that appeared in August 1918 that was the most deadly wave of the two-year pandemic. The first death in Maine occurred Sept. 23 when William E. Lawry, a 36-year-old, died at his home in Augusta. Lawry likely passed the illness on to many more people.

The epidemic had reached Aroostook County by Nov. 7, with the town of Caribou particularly hard hit. The Bath and Brunswick areas were also hit hard due to a temporary population spike after workers flooded into Bath Iron Works to contribute to the war effort.

For a bit of historical context: World War I officially ended Nov. 11 of that year in the midst of the pandemic. An estimated 37 million military personnel and civilians died during the war. During the latter half of 1918, many millions more than that died from flu.

By late December the epidemic had slowed down, though cases were reported well into 1919. Between September 1918 and May 1919, around 5,000 people in Maine died from the flu or associated causes, such as pneumonia or pregnancy complications. Of those 5,000 deaths, around half were in the month of October, and around half were of people between 20 and 40 years old. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Maine’s population in 1918 was about 760,000, meaning around 1 percent of Maine’s population died from flu — it is widely thought by health officials and historians that Maine’s official estimates of the numbers of flu cases and deaths were quite low due to the rapid spread and virulence of the disease and inconsistent recordkeeping.

In Bangor, nearly 1,000 cases of flu were reported during October 1918, along with 53 deaths. More cases and deaths occurred in November and December. All told, nearly 1 percent of Bangor’s total population of around 25,000 died over the course of three months — not far off from the estimated statewide percentage of deaths from flu.

The flu pandemic had a major effect on Maine, not just in terms of loss of life. Prior to 1918, health boards were a patchwork of local offices, all with differing opinions on how to best promote public health. After the pandemic, oversight shifted from municipalities to the state, and the Bureau of Health was formed. In 2005, the health bureau became known as the Maine CDC, a part of the newly merged Maine Department of Health and Human Services.

In several towns and cities, Catholic churches fought to stay open during the pandemic, with a priest in Lewiston going so far as to argue that the health of the soul was equally as important as the health of the body. In fact, Maine’s Roman Catholic diocese struck a bargain with several towns, saying it would open a hospital in Maine if they let them continue holding mass during the pandemic. Portland took the bargain, and Queen’s Hospital — today known as Northern Light Mercy Hospital — was founded in 1918.

The closest modern comparisons to the Spanish flu of 1918 were the “Hong Kong” flu outbreak of 1968, which killed more than a million people worldwide, and the 2009 H1N1 outbreak, also known as the swine flu, a virulent strain that, like the 1918 flu, affected young and otherwise healthy people more than typical flu viruses. The “swine flu” sickened up to 200 million people worldwide, and the U.S. CDC estimates it killed more than 284,000.

The seasonal flu — the one just about everybody gets at some point in their life — happens every year in the northern hemisphere between October and May, with December through March being the deadliest months. It kills tens of thousands of people each year, most of whom are young children, the elderly and the immunocompromised.

According to the Maine CDC, so far during the 2018-19 flu season, 168 people in the state have tested positive for flu as of Dec. 22. At that time a year ago, 373 people had tested positive in Maine. During the 2017-18 flu season, more than 80 people in Maine died from flu complications.

Though many of the same rules apply today as they did 100 years ago when it comes to preventing influenza (wash your hands, cover your cough and stay home when you’re sick), there’s one big thing that’s different today: the influenza vaccine.

Alongside health care providers, nearly every major pharmacy across the state offers walk-in flu shots — something the CDC recommends every year for all people older than six months.

This article originally appeared on www.bangordailynews.com.