ASHLAND, Maine — The Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry is in the midst of taking public comments on proposals aimed at stopping the spread of two forest pests — the gypsy moth and the emerald ash borer.

The DACF held a public hearing on the quarantine proposals Monday, Feb. 11, in Ashland, and will be taking written comments until Feb. 25, said Gary Fish, state horticulturist with DACF.

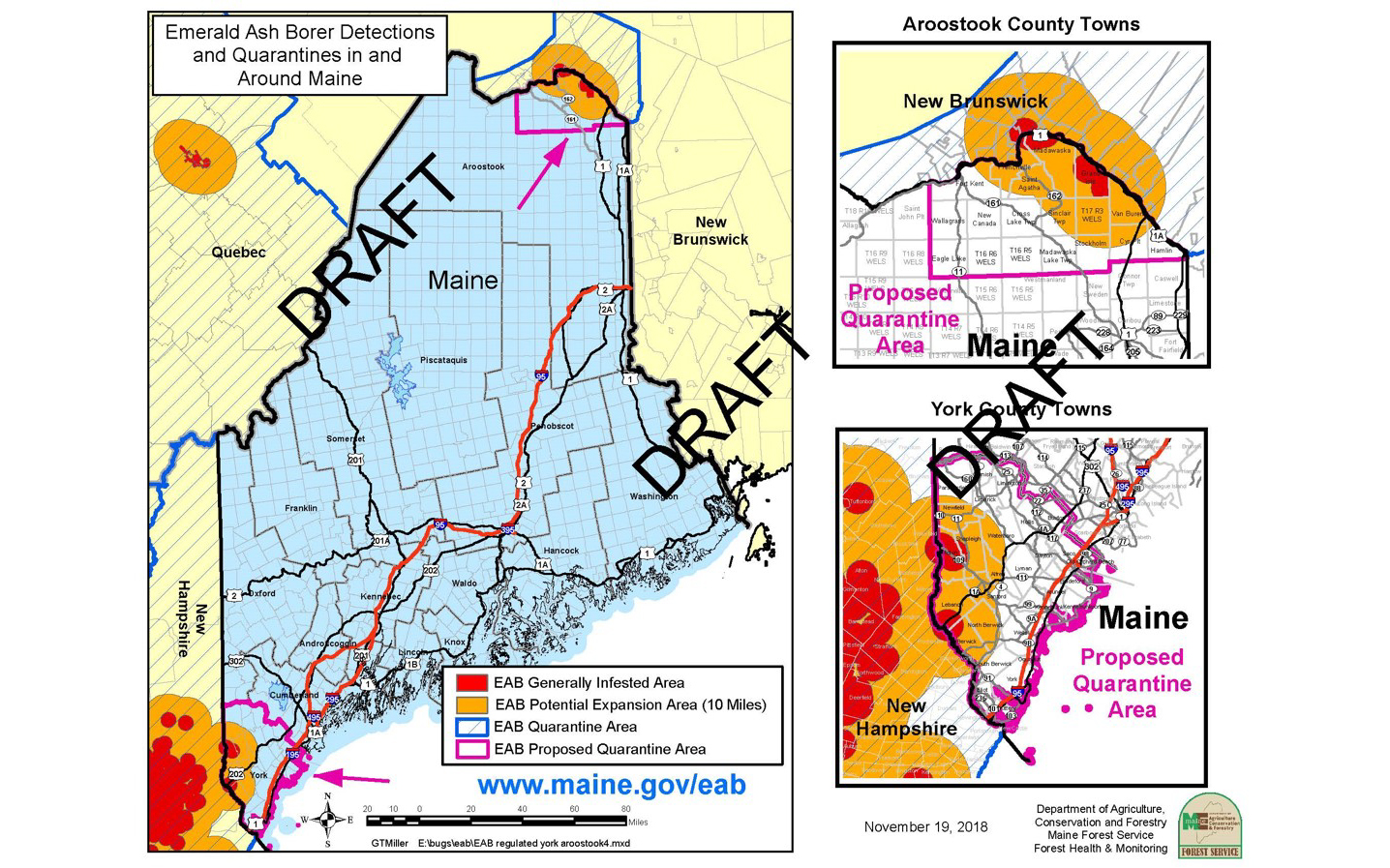

The proposals would establish new quarantine areas restricting movement of harvested trees in parts of Aroostook County and elsewhere in an effort to curb the movement of the gypsy moth and the emerald ash borer. The former is a long-time pest of many kinds of trees and the latter is a new-to-Maine pest of ash species.

Both quarantines are required by the federal government, and if the state didn’t implement its own, the U.S. Forest Service would likely put in place quarantines across the entire state, Fish said.

For the gypsy moth, there has been a quarantine on large parts of Maine for many years, but the proposal would add new areas along the northern tier of the state from Oxford to central and western Aroostook County, the horticulturist said.

Gypsy moths are caterpillars originally imported from Europe in the early 1900s as potential silk producers, and they feed on a wide variety of trees and shrubs, particularly oaks. They’ve been in Maine almost 100 years, with populations kept in control by diseases associated with wet springs, Fish said.

A map of proposed additions to the current quarantine areas for gypsy moth.

(Courtesy of Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry)

However, in recent years they’ve caused severe defoliation in parts of southern New England during dry springs, Fish said, adding that three years of defoliation can kill a tree.

“Areas that don’t have them don’t want them. If you’re shipping trees from Maine to New Brunswick, where there is no gypsy moth, that’s why we need the quarantine. If the state doesn’t expand the quarantine, the USDA most likely would put the whole state under quarantine.”

Under the proposal, movement of trees from the quarantine zones will be allowed but with a compliance agreement with the Maine Forest Service that ensures actions are being taken to not spread the insect’s eggs, Fish said. For instance, logging operations would have to sort their logs and keep track of which ones came from areas under quarantine.

“It does create some extra steps that they’ll have to take to move wood during certain parts of the year,” he said.

So far, no one has registered opposition to the gypsy moth or ash quarantines, Fish said.

“There’s a good part of The County that’s already been under the gypsy moth quarantine. This adds about 105 towns to the quarantine, from Oxford to Aroostook,” he said.

The ash quarantine proposal would place all of York County and much of the St. John Valley under quarantine for ash species to try to deal with the emerald ash borer, which was first found in Maine last spring in Madawaska.

“The current stop movement order is only for Madawaska, Frenchville and Grand Isle,” Fish said. “This adds towns all around those going to Fort Kent, down to Eagle Lake, then east to Hamlin, and also all of York County.”

“The big difference between this one and the gypsy moth is this really impacts firewood dealers, because it includes restrictions on any kind of hardwood firewood, not just ash.”

Under the proposal, any hardwood firewood from the quarantine area could just be sold locally. If it is sold outside the area, it would need a compliance agreement, which needs to be approved by the federal government, Fish said.

He said that at least one major firewood dealer, J.R.S. Logging of Fort Kent, would be affected, but the state is looking to work with the federal government to allow companies such as J.R.S. to continue selling non-ash firewood from the quarantine areas.

“We’re negotiating with federal government to allow J.R.S. Logging and potentially others that can show us that they don’t cut ash,” Fish said. “That’s not assured at this point.”

Ash trees comprise about 4 percent of Maine’s hardwood forestlands, and are an important cultural resource for the state’s four Wabanaki tribes.

Fish said that ash trees could be harvested commercially from the quarantine areas with compliance agreements that ensure no movement during May to September, when the emerald ash borer adult beetle is flying.

The quarantine also affects ash nursery stock, although most nurseries no longer sell ash, the horticulturist said.

Fish said the DACF is recommending that landowners not plant ash species and also advising them not to harvest all their ash. The long-term goal of Northern American forestry experts and tribal communities is to support native ash species that are resistant to the ash borer and to protect new generations through parasitic wasps that prey on the borers.

“From 2002 until now, starting in Detroit, about 99 percent of all the infested ash succumbed,” Fish said, referring to when the ash borer was first found in the U.S.

“There are outliers that are resistant and some that seem to have little damage. There is a movement within the U.S. Forest Service to try to find those trees, protect them and have both male and female ash that survive to breed a resistant tree for the future. As populations move, in Maine, there will be releases of three parasitic wasps that only feed on borer larvae,” Fish said.

“It’s promising but not guaranteed,” Fish said. “We’re advising landowners to not cut all the ash, to leave some behind to see if there are some that will survive.”